Collaborative Achievement: Three Lessons from Apollo 11

Sunday 21 July 2019 marked 50 years since the Apollo 11 moon landing.

The landing was a monumental human achievement, and one rightly commemorated with some genuinely moving and meaningful tributes.

There are some important learnings from the mission about what it takes to succeed, and how shared purpose can be realised. Here are my top three…

1. The Power of a Clear, Ambitious Goal

“I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth” President Kennedy said in a special address to Congress in May 1961.

That landmark speech galvanised the nation and paved the way for the success that was celebrated last weekend. It’s tempting to focus on the end result without remembering there was a solid eight years of research, work, tests, failures and innovation before Apollo 11 landed on the moon.

And all that work was focused by the combined ambition and clarity of that statement.

Rarely has a public policy goal been so clearly specified (in advance!) in substance and in timing. The usual temptation is to keep things vague so that if they don’t work out, there is no failure, embarrassment or recriminations. The other trick is to claim credit for a success after the event.

While these are understandable and altogether human tendencies, this nebulousness and lack of accountability, ironically, has the effect of militating against success. The reason isn’t hard to see: how can you accomplish something if it’s not clear what you’re accomplishing? There is simply no force to galvanise people’s efforts if the end-state is not properly specified. It will be up to the whim of a leader’s interpretation and this will likely be dictated by the small ‘p’ politics of the day: hardly inspiring, and unlikely to produce success.

- How well specified are your organisation’s goals? Are they singularly clear enough for all to know whether they’ve been met? Or do you have the (fake) luxury of being able to duck and weave?

2. Welding Individual Effort into Joint Performance

It took around 400,000 people to land humankind on the moon according to astronaut Michael Collins. That is a massive effort which requires a multitude of elements to be managed in a collaboration as successful as Apollo 11’s; however here’s my starter list:

- clear programs of work and accountabilities and action plans for their implementation

- regular and persistent follow-up

- policies and procedures

- clear feedback of results against expectations

- a constructive, positive culture which is oriented to problem solving, forward movement and evidence-based decision-making

- sufficient resourcing in terms of skills and budget, and

- attentive and supportive leadership to oversee the effort.

But there is one more. It’s one thing to organise human effort with policies and procedures, programs and action plans, and a constructive culture in which people can participate: all of these are right and necessary. But there is something else again which flows directly from the first factor noted above, which is to inspire people to perform and bring out their best, and it is the ambition and clarity in that goal which does so.

In the same speech, JFK said “…if we make this judgment [ie. to put a man on the moon] it will not be one man going to the moon, it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.” That statement transformed the space project from being a public policy goal (up there with establishing the AID program, and expanding the NATO alliance, both of which featured in the same speech) to being a statement of collective vision, national pride and an aspiration in which all could participate and see themselves. That is the key factor welding individual effort into joint performance and it is the animating impulse behind any great collaboration.

- How ‘welded together‘ are the efforts of your staff? What joint performance is your organisation or unit accomplishing? Are people inspired to see themselves participating in something greater than the sum of its parts?

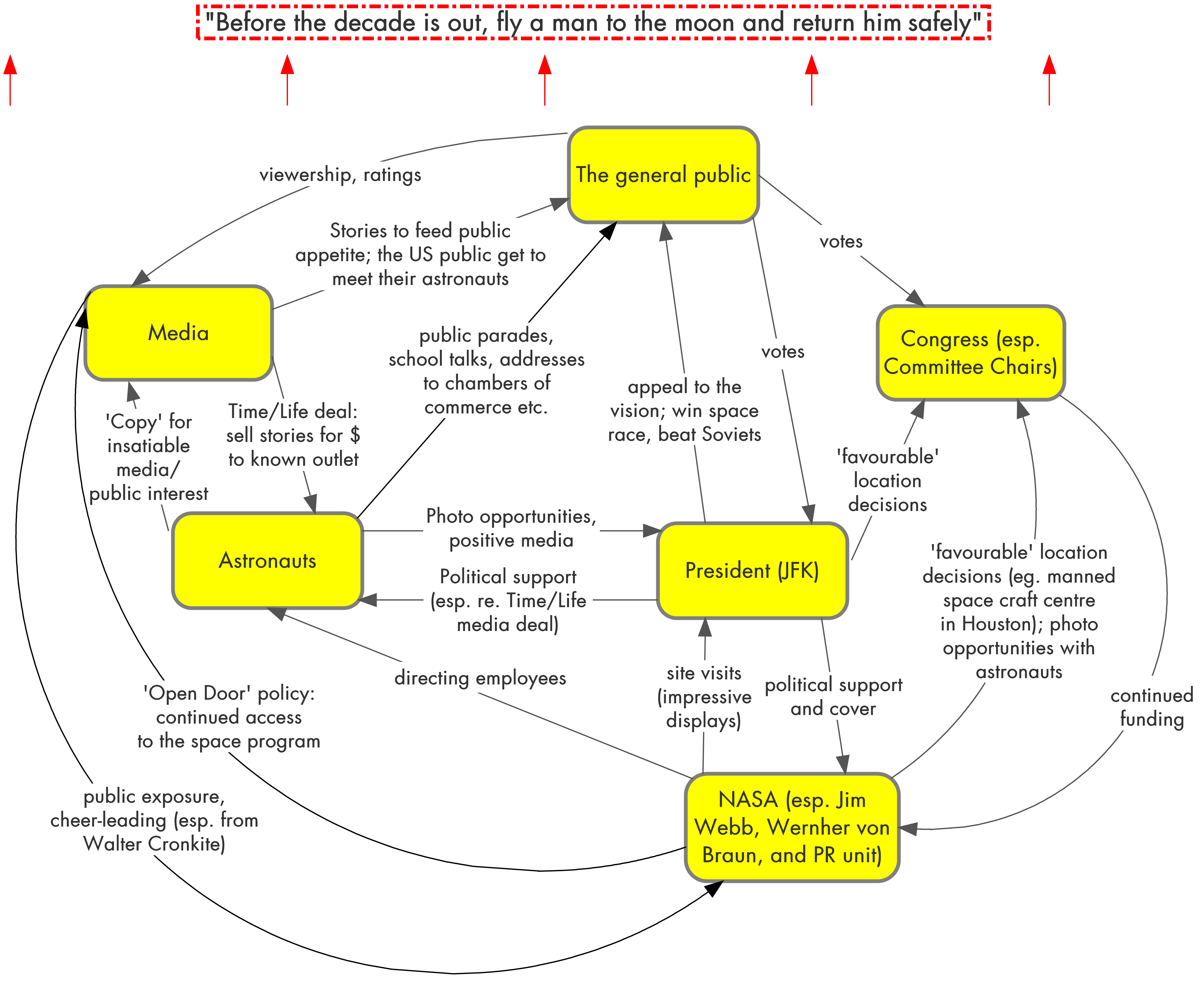

3. Aligning Critical Stakeholders

No collaboration can survive without attending to the needs of stakeholders and securing their support.

Apollo 11 was not a purely technical accomplishment – the scientific and technical aspects were key, but were not the whole story. Many worthwhile programs have been scuttled by organisational politics or shifting demands from the various players in their respective positions on the stakeholder terrain, despite their technical merits.

NASA was very attuned to its stakeholders and their needs: when there was concern about cost blowouts early in the program, and that the President’s support might wane, JFK was invited to a demonstration at the space centre in Huntsville Alabama. A rocket booster with 32 million horsepower was fired up for 2½ minutes, which JFK said at the time was the most impressive thing he’d ever seen. Unsurprisingly then, support (and funding) for the program continued.

The diagram below is my depiction of the various stakeholders and their ‘leverage points’ in the early years of the space program. Note the array of incentives and the often two-way movement of pressure and benefits:

© Michael Carman 2019

- Who are your organisation or program’s key stakeholders, and how well have you comprehended their needs and attended to those?

* * *

The space program of the 1960s is instructive in many regards for executives and decision-makers; with the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11 it’s salutary to take from those learnings what we can and bring some of NASA’s success to our own efforts.

And as always, if you’d like a hand crystallising a clear and ambitious goal, welding individual effort into common purpose, or identifying and marshalling stakeholders, just give me a hoy.

Warm regards,

Michael

References:

Chip Heath and Dan Heath (2008) Made to Stick Random House, pp.95-6.

PBS (2019) Chasing the Moon [video file].

© Michael Carman 2019